Almost every scribe I’ve talked with shares some apprehension when facing a blank wall at the onset of a session. Many of us are introverts by nature, and need to summon courage to even be at the front of a room, audience at back.

As we try to follow cadence of voice and quickly make sense of streaming words, accents, acronyms, metaphors–and just as quickly choose what to draw–confidence goes down, and questioning of self goes up: “Am I worthy? Why do they want me here anyway? What on Earth am I drawing? Will anyone notice if I crawl up and hide behind this easel?!

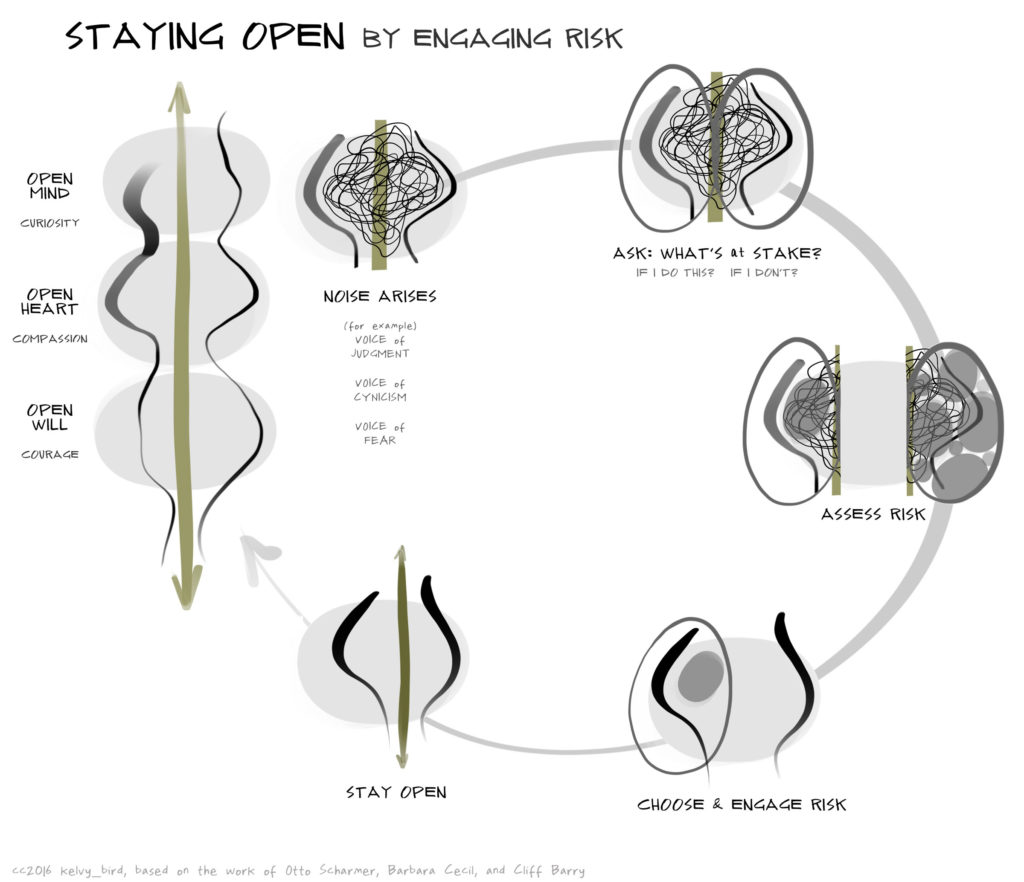

The line “I can’t….” creeps in easily and perennially. And unless we learn how to notice this running tape in our heads and abruptly turn it off in favor of another line, it’s really, really easy to get psyched out and freeze. It’s a slippery downhill slope.

I’ve also heard countless people say, “What you do seems so cool, but I can’t draw…” To which I almost always respond “Oh–you would be surprised how little it takes…”

Recently, to strengthen my (physical) core, I’ve enlisted the help a personal trainer, Carl. When he asks me to try a new exercise, of which I can barely do one repetition, I often find myself moaning “Oh, man, you have GOT to be kidding! I can’t…!” He stops me in my tracks: “Once you decide you can’t, you’ve pretty much guaranteed you won’t.”

“I can’t” is a belief.

It festers in (some of our) psyches, ripe to bolt out and take the stage at the slightest challenge. It’s belief that I am, for example: not strong enough to lift a particular weight, not capable of staying fit over time to even be at the gym. Sometimes it’s not about what I can or can’t do, but is about who I am. The line in this case would be “I am, by nature, lazy.”

And here is where judgement comes in, residue from past experience that leads to the formation of belief. Something happened, we felt embarrassed, rejected even. Shame might have set in, reinforcing future choices and outlook.

As a young girl, I played municipal softball with great enthusiasm. Then at some point, I tried out for a local basketball squad, and–after falling flat on my face when attempting a layup–was the only girl who did not make the team. My enthusiasm for sport quickly dwindled. And now, some 35 years later, I have Carl’s voice helping to turn around an old, hardened belief that I am inherently unskilled at physical activity.

Maybe “I can’t” is a kind of stop sign, a temporary pause until we turn the light in our mind green. We face a choice point: collapse into old attitudes, or face this moment fresh, opting new possibility?

Maybe every “can’t” is really a gift in disguise, a twisted offering to reframe within the present to a mindset of “if”?