To frame is to convey boundaries, limits, and openings, options. Frames help divide and compartmentalize and also define areas to bridge through relation. The framing of the physical and the framing of our thinking parallel each other, and understanding one can enhance our understanding of the other. Both are needed in visual practice, as scribes organize information in the mind as we organize words and shapes on a page.

the physical

One understanding of a frame is a protective edge of a 2-dimensional form, such as around a window or glasses. Drawn frames can look like boxes or circles that offer visual parameter. The most outer edge of the paper also represents a frame, as do the four walls of a room or lobby that contain a display of completed work.

We frame content to give it contextual coherence. We cluster like-ideas and enclose the grouping with a closed line. But framing is not only about boxing things in, or fitting things together in a way that’s merely convenient.

Framing is ultimately about setting up conditions for choice.

With the proportions and proximity of what we include and exclude, we provide a limit that informs the participant-viewer what is in, what is out. With that information, people can make decisions about how to place themselves relative to the meaning the picture conveys.

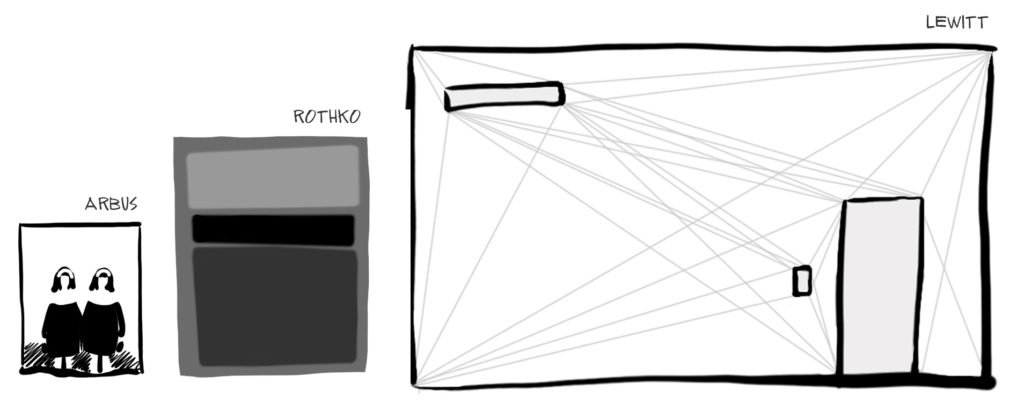

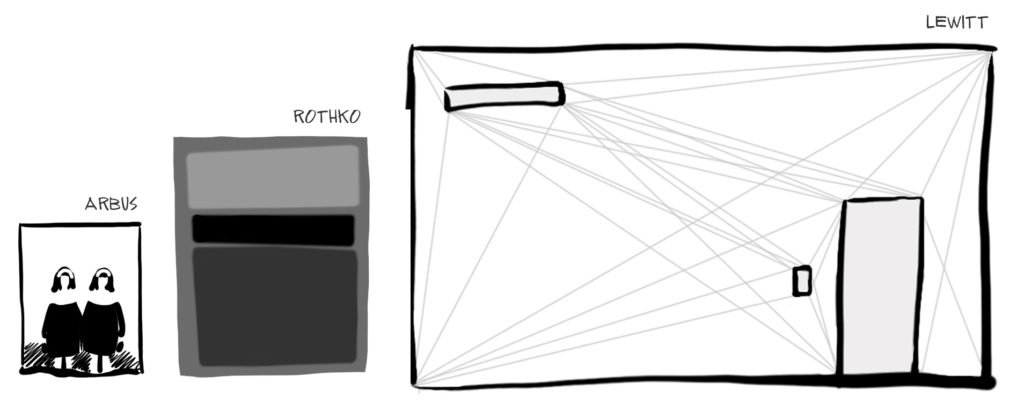

If we look back at some examples from 20th century art, we can see a variety of framing devices that each set up the viewer for different interpretive outcome. This is useful as a guide for how we can consider physical framing with increased intentionality.

The photographer Diane Arbus placed her subjects completely central to the picture, almost forcing our focus to one object, regardless of background. The painter Mark Rothko layered large floating rectangles of deep color, somewhat frame-less, as a means for transcendence. And then Sol LeWitt plays with the frame to break it; rather than complete drawings by his own hand, the artist created “rules” that an installer could use as instruction to draw directly onto the interior surface of any physical environment. One example is “All architectural points connected by straight lines.”[i] The wall is the frame, but the frame changes with every installation.

the conceptual

Framing is also about the lenses we use to organize what we hear and intuit.

I might be listening to a conversation on strategy, for example, and notice data that indicates a conservative approach, a leaning to stay close to existing conditions. People could be saying things like: “Why fix something that isn’t broken?” “I don’t know… things seem to be fine from where I sit…” “We don’t have the capacity to produce 100 additional widgets this year…” What do I interpret from that? An inclination towards safety, preservation. In my mind, I call this frame “current reality.”

And, based on experience, I make the attribution that there might also be low aspiration represented in the room. But there is not yet data to confirm that, so in my mind I prepare an empty frame called “vision” to hold a place for that to come in. It’s like setting out a plate for a meal that is still cooking – because the plate is there, the incentive to fill the dish might increase.

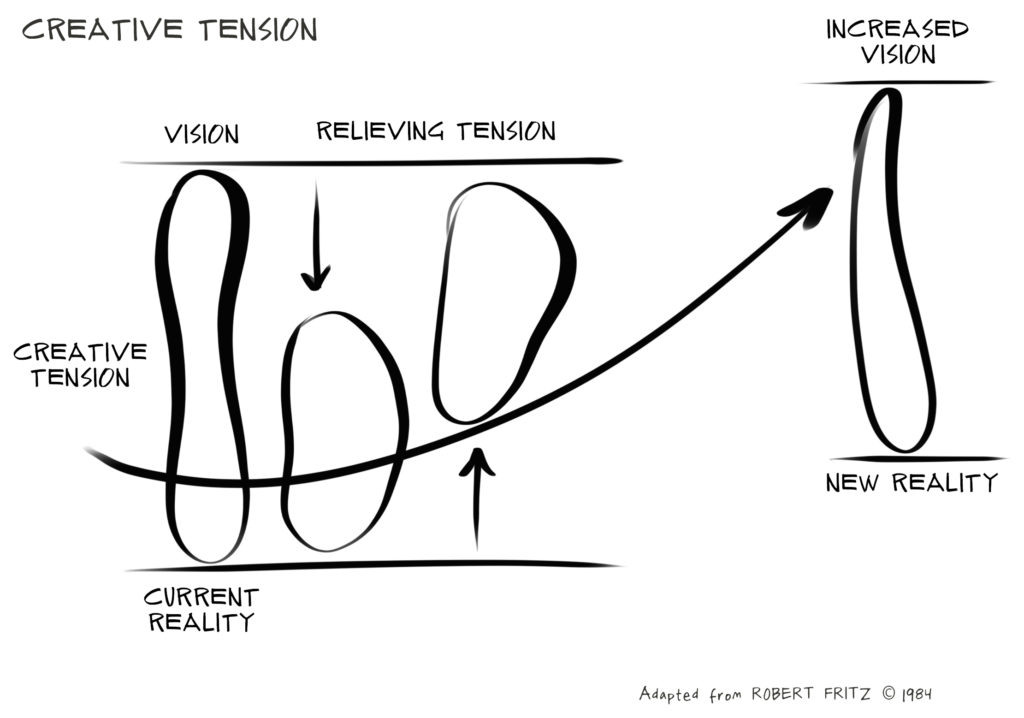

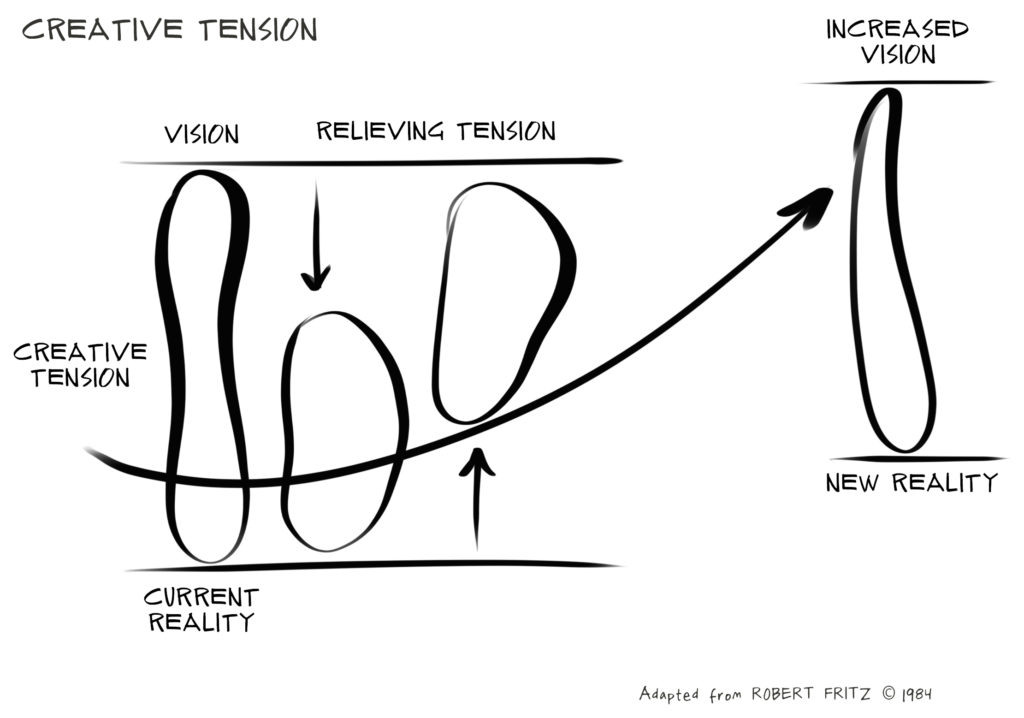

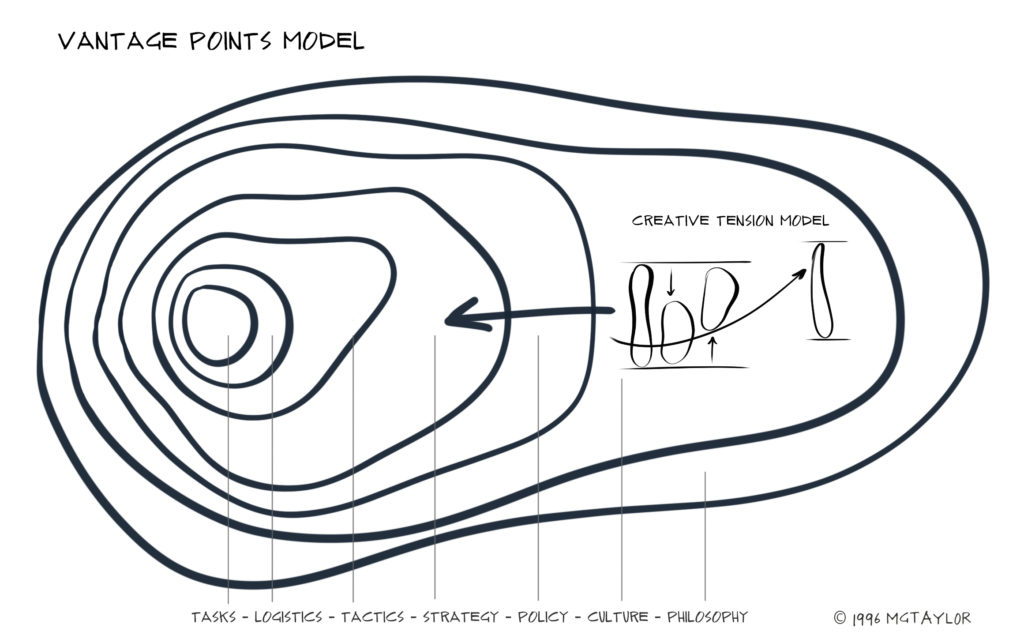

I often bring in models as scaffolds for my thinking. And in this case, Robert Fritz’s Creative Tension model comes immediately to mind.[ii] Often drawn with Current Reality on the bottom, Vision on top, and the middle section representing the creative – or structural – tension between the other two. Fritz states that “tension seeks resolution” and that “one major skill of the creative process is forming structures that resolve in favor of the creation.”

With this in mind, I confirm against the initial client calls and planning that there is actually a stated desire somewhere in the system for a creative outcome from this meeting. If so, in my mind I will hold this kind of framing as a backbone for how I listen:

I will choose within my physical frame to allot a certain amount of the board towards Current Reality, a certain amount towards Vision, the space between for any tensions that surface, and probably space for the New Reality as well as the Next Steps required to get there.

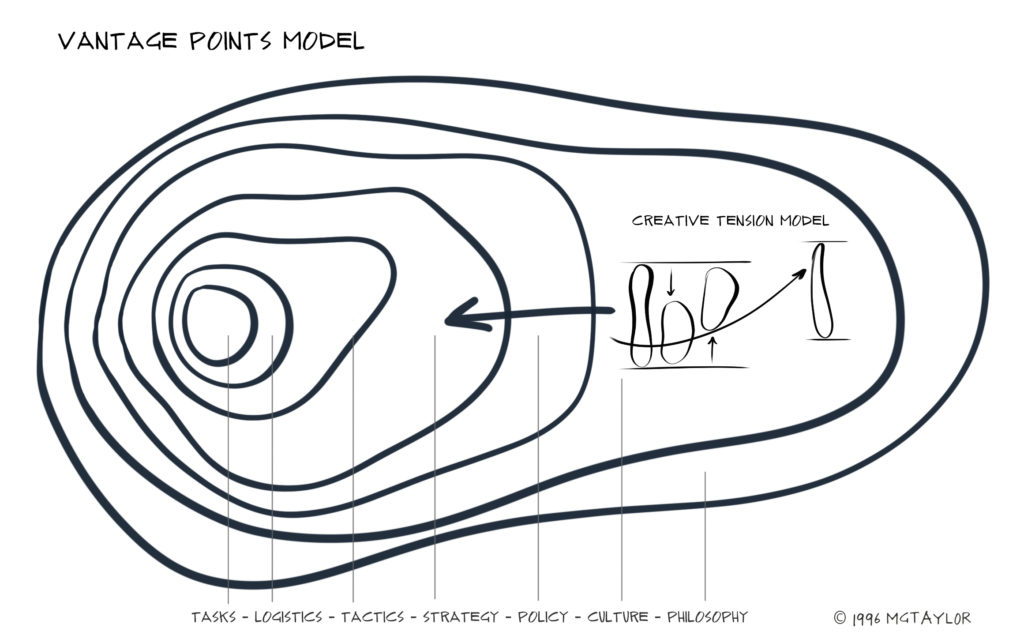

I will have additionally, almost unconsciously, made a quick call to up the ante on the group and place the strategy conversation within a larger cultural context, and listen with that attunement as well.

MG Taylor charted a model called Vantage Points[iii], where Strategy exists close to Culture. Upon hearing the initial leaning into safety from the first few comments, I might have also started to assume some cultural stuckness around vision. I might be asking myself, “Does this group even want to entertain a new reality, a new approach or way of being?” Again, I keep this in mind knowing it’s an attribution, and listen closely for confirming or disconfirming data, before drawing too much in any one direction.

So basically would I overlay two models to help me approach the conceptual framing. In my brain it looks like this:

Granted this is a more facilitative approach to scribing, where internal organizing explicitly influences tangible, visible output. And to pull it off takes some genuine sensing into the tolerance / appetite for growth of a group, combined with careful application of a scribe’s tacit knowledge.

The more sessions we scribe, the more models and theories we are exposed to. It’s a huge advantage in our profession, often traveling as we do between a wide variety of programs, to have this learning luxury built into our work. Take advantage of it and increase your knowledge base! Seek out those whose ideas you admire and do whatever you can to be in the same room. Sketch on a napkin if you have to while they talk. Absorb what you can, whenever possible.

Likewise, study the masters of two-dimensional art to further educate yourself about layout and physical framing options. My dearest college professor, Eleanore Mikus, once gave me the following advice: “Travel alone and get lost. You learn so much. Head for the museums and churches in every country, just keep on going.”

Our path, including how we approach it and how we organize it, is ours to define.

(But that is just my framing on the whole thing!)

[i] LeWitt, Sol. Wall Drawing #51, 1970. “LeWitt’s instructions for Wall Drawing 51 dictate, “All architectural points connected by straight lines.” Using the simplest and most technically precise means available, Wall Drawing 51 comprises hundreds of blue lines of varying length stretching from one architectural detail to another, including door frames, columns, fire alarms, etc. Employing a chalk snap line, a contractor’s tool that is used to create straight lines on flat surfaces, this drawing focuses the viewer’s attention on the architecture of the space.” http://massmoca.org/event/walldrawing51/

[ii] Fritz, Robert. The Path of Least Resistance. Chapter: “Tension Seeks Resolution.” Fawcett Books. 1984.

[iii] http://www.mgtaylor.com/mgtaylor/glasbead/vantgpts.htm